How to Write a Play: Step-by-Step Guide 2025

Learn how to write a play with our 2025 step-by-step guide for students. Master playwriting structure, dialogue, and tips for academic success.

Debates usually have a purpose to bring change, a change in thinking, belief, research, and policy, while they also break the stereotypes. With debates over policies, the national interest can be taken into account, and the bigger picture of change can be considered. The courtroom is a place where narratives are played, and the winner is the best narrator. Be it a complex argument you are presenting or defending a client, it is not only the facts that will make you gain ground, but more so how you structure, strategize, and deliver your points in Policy Debate without any hitch. This is your roadmap to the art of litigation, so that evidence may be turned into a compelling story that appeals to the trier of fact. We are going to find out how to create an airtight case-in-chief, create a story that is both legally valid and emotionally appealing and most importantly, unleash the power of cross-examination when the time and the opportunity to prepare coincide. Train to string a coherent narrative together, counter-movement beforehand, and lead the jury to your conclusion.

When questions like what is policy debate or how to start it arise, then you must know that it is a two-on-two debate, also known as cross-examination debates, that centers around one national policy resolution, which is debated the entire academic year. The Affirmative team has a proposal to change the present policy, and the Negative team opposes the plan, usually on the grounds that the current policy is better or the new plan is disadvantageous.

Policy Debate is unique with its full-year attention to one complicated national policy solution, and it needs immense research. It is the most evidence-intensive type of debate that provides direct quotations of each assertion. The Negative is unique in that it is able to bring a complicated approach, such as Counterplans and Kritiks, hence it is very technical and deep in its strategy.

The policy debate format or rounds are conducted on a very rigid timetable of giving speeches and cross-examining in alternate order, so that both teams have equal time to make their arguments and disprove the opposition, the complete guide to debates can be your roadmap. The round is an exhausting schedule of premeditated presentations and improvised interactions, time-constrained on each individual part.

| Speech | Abbreviation | Time | Speaker | Primary Purpose |

| 1st Affirmative Constructive | 1AC | 8 minutes | Affirmative | Present the complete affirmative case |

| Cross-Examination | CX | 3 minutes | Negative questions Aff | Clarify and challenge 1AC |

| 1st Negative Constructive | 1NC | 8 minutes | Negative | Present negative positions and arguments |

| Cross-Examination | CX | 3 minutes | Affirmative questions Negative | Clarify and challenge 1NC |

| 2nd Affirmative Constructive | 2AC | 8 minutes | Affirmative | Respond to all negative arguments |

| Cross-Examination | CX | 3 minutes | Negative questions Aff | Clarify and challenge 2AC |

| 2nd Negative Constructive | 2NC | 8 minutes | Negative | Extend key arguments, begin crystallization |

| Cross-Examination | CX | 3 minutes | Affirmative questions Negative | Final clarification |

| 1st Negative Rebuttal | 1NR | 5 minutes | Negative | Extend key voting issues |

| 1st Affirmative Rebuttal | 1AR | 5 minutes | Affirmative | Rebuild affirmative case |

| 2nd Negative Rebuttal | 2NR | 5 minutes | Negative | Final negative summary |

| 2nd Affirmative Rebuttal | 2AR | 5 minutes | Affirmative | Final affirmative summary |

Each policy debate round is allotted a predetermined amount of time for preparation, which usually ranges between 5-8 minutes in total per side, which may be spent wisely in the debate. Exploring the Public Forum debates can also be helpful in underestandin the proper roadmap.

The primary activity of the Affirmative team is to deliver a strong, backed-up argument that will demonstrate that the existing policy is unsustainable, and their particular Plan is a welcome solution. This is the framework of how does policy debate work and on which that case is built.

An Affirmative case in policy debate is conventionally based on the Stock Issues, which reflect the very questions to be answered yes to make the Affirmative win. They serve the purpose of being the heavy lifting that the Affirmative has to pull through.

Although the Affirmative case, too, necessarily still implicitly treats the Stock Issues, the contemporary argument can tend to be structured into a more strategic or more philosophical style:

The Policy debate format is an evidence-based process that demands strict criteria for all applied sources.

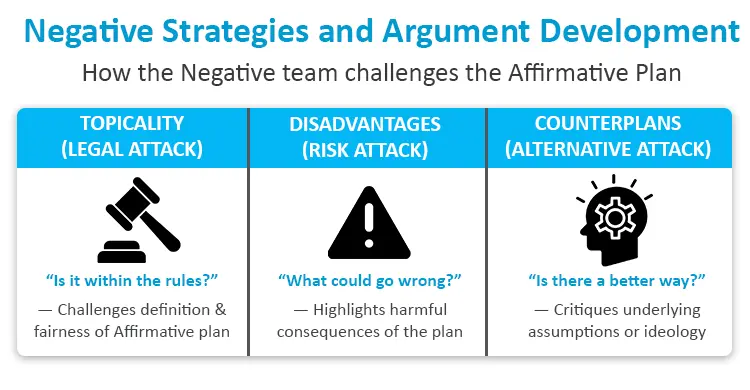

The Negative team employs three arguments to destroy the Plan of the Affirmative. Consider those three angles of attack, the Legal Attack, the Risk Attack, and the Alternative Attack.

The topicality is a procedural argument that challenges the legality of the Affirmative existing in the debate. It would request the judge to come in, but not because the scheme is a bad one, but because it is against the regulation of the game.

The Disadvantages is a policy argument that evaluates the dangers of adopting the Affirmative Plan. It is concerned with the possible adverse ripple consequences.

The Counterplan is an alternative policy that is supposed to remove the thunder of the Affirmative. It concurs that the issue should be resolved, but provides a more efficient and secure way of doing so.

The Kritik is a more philosophical type of argument that questions the basic assumptions, language, or the underlying ideology of the case of the Affirmative in question, and not the text of the policy. The four essential components of a K are discussed:

The essential three minutes of cross-examination are the time during which a debater is in full control of the conversation, elucidates points, and previews attacks they will use in their further speeches. Successful CX can be seen not as an argument, but rather as an exchange of concessions and information.

The aim of cross-examination varies based on the speech completion just made and the items that the questioner must achieve in the following constructive or rebuttal.

Simple and directed questions are the best cross-examiners because they are intended to obtain a brief answer that can be exploited in a subsequent oration.

Being in control and displaying professionalism is what will be required to ensure maximum impact of cross-examination.

The most important note-taking system in Policy Debate format is called flowing. It also enables debaters to follow all the arguments presented during the round so that nothing is dropped. It contains a visual account of the whole debate, and it acts as a memory and roadmap to the debater.

A flow sheet is usually a collection of giant pages devoted to a particular speech and argument. It is very standardized in its structure to make it easier to refer to and organize.

The policy debate structure tends to be rather rapid, and in this case, the debaters are supposed to design effective methods to absorb massive information within a short period of time and with high precision.

| Technique | Description | Examples of Shorthand |

| Abbreviations & Symbols | Using shorthand for common words, concepts, and policy terms to save time. This is the most crucial technique. | DA (Disadvantage), CP(Counterplan), K (Kritik), T (Topicality), w/ (with), w/o (without), > (more/better), < (less/worse) |

| Vertical Stacking | When writing down a series of sub-points or evidence tags, debaters write them vertically down the column, stacking the points. | Harm → $H_1$, $H_2$, $H_3$ |

| "Clipping" and Focus | Debaters focus on writing down the tagline (the summary) and the source citation (cite) of the evidence. They do not write the entire quote. | Write "Smith '23: Econ Growth" instead of the full evidence. |

| Color-Coding | Using different colored pens or highlighters can instantly separate argument types or highlight key claims. | Negative arguments in blue, Affirmative answers in black. Impacts circled in red. |

| Skipping | Less important points or arguments that are conceded are skipped entirely to focus effort on the high-priority "voting issues." | Ignore irrelevant organizational points to focus on the Link of the DA. |

The official national policy debate topics for the current and upcoming academic years are determined by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) for high school debate and the Cross Examination Debate Association (CEDA) for college debate.

| Competition Level | Resolution (Topic) |

| High School (NFHS) | Intellectual Property Rights: "The United States federal government should significantly strengthen its protection of domestic intellectual property rights in copyrights, patents, and/or trademarks." |

| College (CEDA) | Clean Energy: "The United States Federal Government should adopt a clean energy policy for decarbonization in the United States, including a market-based instrument." |

| Competition Level | Resolution (Topic) |

| High School (NFHS) | Arctic: "The United States federal government should significantly increase its exploration and/or development of the Arctic." |

| College (CEDA) | Labor: The broad topic area selected for the college circuit is Labor, with the final resolution text to be announced. |

A team that follows an advanced strategy will use glamorous tactics to distract and confuse the opponent, with great attention to time management to put forth logically clear and sound reasons for the judge to vote for that team.

In continuing your learning journey, use the major policy debate organizations for official resolutions and rules. Intensive training and advanced strategies may be offered in summer institutes. For setting a strong foundation, brush up on the essential textbooks and research databases to gather quality evidence and deepen your understanding of the annual topic.

Policy Debate is an arduous and evidence-intensive activity that requires a deep understanding of complicated policy and a strategic performance aspect. Success depends on building a sound case structurally, using powerful Negative strategies such as DAs and Counterplans, and employing a meticulously organized Flowing system. Those tools are then used by the master debater to construct the round into a clear, persuasive, and decisive winning narrative.

Policy Debate involves an in-depth study of a single subject over a full year with a particular emphasis on evidence read out of pre-prepared cards. Parliamentary Debate employs a new topic in every round, and uses logic, rhetoric, and general knowledge to argue instead of a lot of pre-round evidence.

Pay attention to scholarly magazines, government documents, and reliable publications of think tanks. Find evidence of high-quality and peer-reviewed evidence using university research databases such as JSTOR or academic Google Scholar. These give your evidence cards the required depth and authority.

Begin by studying the structure and main arguments. Participate in a local team/club, practice on a regular basis, and do research on the national issue at hand. Find a partner with experience to assist and read the essential evidence.

Speed is very crucial as it gives you time to read more evidence and make more arguments within a short duration of time, which helps in overwhelming the opponents and makes all the points needed. But loudness is of no use; the judge should be in a position to listen to and comprehend your points in order to cast his ballot in your favor.

Subscribe now!

To our newsletter for latest and best offers