How to Write a Play: Step-by-Step Guide 2025

Learn how to write a play with our 2025 step-by-step guide for students. Master playwriting structure, dialogue, and tips for academic success.

Parliamentary Debate can appear to an outsider as a form of verbal duel with very high stakes, and a confusing one. Nevertheless, this is a dynamic format where teams argue over a motion, and they have minimal to no preparation time, which is among the most popular and most intellectually fulfilling competitive activities in the world. It is a furnace for cultivating keen, incisive thinking, volley thinking, and persuasive oratory, which is priceless in any profession. Parliamentary debate competitions on college campuses to world championships compel students to not only learn how to improvise an argument but also enact the particular, time-tested roles of a legislature. Dreaming of being a government representative or opposition, the principles of format, playing the role, and planning approach will be necessary.

This guide will bring you to the inner part of the debating room, provide you with the overall picture of the significant formats, discuss each role of speaking thoroughly, and furnish you with winning, time-tested tactics that you must employ to win the vote and, eventually, the debate.

A particular, spontaneous variety of formal argument, parliamentary debate, is based on the legislative practices of governments, usually those based on the Westminster system. The origins of the competitive parliamentary debate format are directly in the format of the parliamentary procedure, as well as the traditions of the British Parliament, namely the House of Commons in the Palace of Westminster. Before the other aspects you must know how to start a debate that impacts the audience most. The most important aspect of it is that moments preceding the start of the round, debaters are given a motion, which forces them to make quick analyses and improvise. Teams are separated into one Government side, which favors the motion, and on the other, an Opposition side, which disapproves of the motion. Speeches occur in order, and an essential factor is the use of so-called Points of Information, during which an opponent interrupts a speaker briefly to ask a question, and they create a really dynamic and interactive event of wit and logic.

In contrast with evidence-based formats, parliamentary debate gives a preeminence to spontaneous logic, quick wit, and rhetoric. Although all major styles are extemporaneous, they differ in several decisive aspects. The British parliamentary debate style worldwide is played by four teams; the World Schools Style is played by two three-player teams, and the World Schools Style is a combination of preparation and mixes the two-person American Parliamentary style with specific case rules. These unique structures are important in learning how to compete.

| Format | Teams | Speakers | Preparation Time | Key Characteristics |

| British Parliamentary (BP) | 4 teams (2 per side) | 8 speakers | 15 minutes | World Universities format, competitive dynamics between teams |

| American Parliamentary (APDA) | 2 teams | 4 speakers | Varies | Oldest US format, emphasizes wit and rhetoric |

| National Parliamentary (NPDA) | 2 teams | 4 speakers | 20 minutes | Most common US format, 7-8-8-8-4-5 speech times |

| Asian Parliamentary | 2 teams | 6 speakers | 30 minutes | Hybrid format, popular in Asian competitions |

Also called World Style, which it bears at the World Universities Debating Championship, the british parliamentary debate format is a four-team format with an emphasis on strategy, originality, and engagement. In a BP debate, there are two teams of two speakers, and the topics discussed are whether the motion should pass or not. The legislative bodies have their teams arranged in a horseshoe formation, and the names of the teams are based on their rank:

| Team | Acronym | Side | Primary Role |

| Opening Government | OG | Proposition | Define the motion and present the primary case. |

| Opening Opposition | OO | Opposition | Directly refute the OG and present the primary Opposition case. |

| Closing Government | CG | Proposition | Introduce a substantive extension (new, significant argument) that does not clash with the OG's material and refute the Opposition. |

| Closing Opposition | CO | Opposition | Introduce a substantive extension that does not clash with the OO's material and provide a final layer of refutation across the board. |

| Speaker | Team | Role |

| 1. Prime Minister (PM) | OG | Constructive Case |

| 2. Leader of the Opposition (LO) | OO | Refutation & Constructive Case |

| 3. Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) | OG | Refutation & Case Rebuild |

| 4. Deputy Leader of the Opposition (DLO) | OO | Refutation & Case Rebuild |

| 5. Member of Government (MG) | CG | Refutation & Extension |

| 6. Member of Opposition (MO) | CO | Refutation & Extension |

| 7. Government Whip (GW) | CG | Summary/Refutation (No new arguments) |

| 8. Opposition Whip (OW) | CO | Summary/Refutation (No new arguments) |

The most popular type of collegiate parliamentary debate in America is American Parliamentary, which is usually held on the American Parliamentary Debate Association and National Parliamentary Debate Association circuit. It is basically a two-team format that involves dynamic interactions, logical and humorous interactions quite commonly.

| Speaker Name | Team | Time | Type |

| Prime Minister Constructive (PMC) | Government | 7 min | Constructive |

| Leader of Opposition Constructive (LOC) | Opposition | 8 min | Constructive |

| Member of Government Constructive (MGC) | Government | 8 min | Constructive |

| Member of Opposition Constructive (MOC) | Opposition | 8 min | Constructive |

| Leader of Opposition Rebuttal (LOR) | Opposition | 4 min | Rebuttal |

| Prime Minister Rebuttal (PMR) | Government | 5 min | Rebuttal |

| Speech | Speaker Responsibility |

| PMC (7 min) | Presents the motion/case; introduces all Government arguments. |

| LOC (8 min) | Directly refutes the PMC; introduces all Opposition arguments. |

| MGC (8 min) | Refutes the LOC; rebuilds the Government case. |

| MOC (8 min) | Refutes the MGC; rebuilds the Opposition case; makes final Opposition constructive points. |

| LOR (4 min) | Summarizes the entire round from the Opposition perspective; identifies key clash points (voters); no new constructive arguments. |

| PMR (5 min) | Summarizes the entire round from the Government perspective; identifies key clash points (voters); no new arguments. |

| Feature | APDA (American Parliamentary Debate Association) | NPDA (National Parliamentary Debate Association) |

| Topic Style | Highly flexible. Case Debate (Government team chooses and writes their own case/motion) is common. Topics can range from policy to literature and philosophy. | Motion Debate. Topics (motions) are set by the tournament/tabroom, and both teams get preparation time for the same motion. |

| Preparation Time | Opposition typically receives no preparation time for the Government's case (they hear it announced in the round). | Both teams receive a set amount of preparation time (often 20 minutes) after the motion is announced. |

| Evidence | Strong emphasis on general knowledge, critical thinking, and accessibility to a "lay judge." | While still non-evidenced, the argumentation can sometimes be more dense and technical, often incorporating philosophical or critical arguments (Kritiks). |

| Flexibility | Higher flexibility; a Government team can run a "loose link" case that is broadly related to the published topic area. | Tighter adherence to the announced motion; less room for novel case interpretations. |

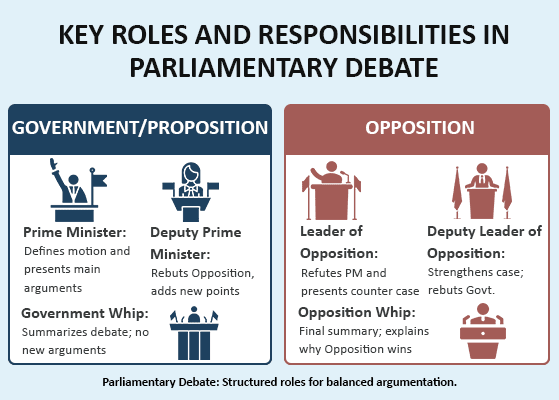

Parliamentary debate is a popular form of competitive speech that separates the participants into two groups, the Government and the Opposition. Each party will have its own speakers with certain responsibilities inherent in the development of opposing arguments. These positions serve to have a well-organized and in-depth discussion of the motion.

The Government, or the Proposition side, has the duty of championing the presented motion. Their main aim is to persuade the audience and the judge that the motion is proper or that it should be passed.

It is the duty of the Opposition side to counter and overturn the motion. Their intention is to demonstrate the falsehood, maleficence, or that the status quo or their version is better.

In addition to the particular roles of the debaters, a body of refined rules controls parliamentary debate topics in order to provide fair, orderly, and dynamic interaction. These steps contain the flow of the speeches, enable questions and challenges on the spot, and organize the short time of preparation. As well as being essential in competing effectively, it is important to follow these rules in order to ensure that the proceedings are well-behaved.

The points of information are short interventions that the members of the opposite party may give out when delivering a constructive speech.

These points are invoked to reflect procedural problems or any personal discomfort, and this remains under strict rules.

About 15-30 seconds before the argument, the preparation itself, also known as prep time, is the limited time during which the teams should have the chance to do research, prepare their arguments, and perform role division.

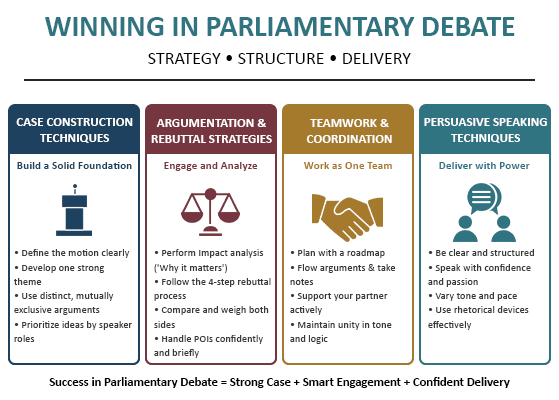

Winning in parliamentary debate requires a strategic blend of precise case construction, aggressive yet structured engagement with the opposition, and effective delivery. Success hinges on a team's ability to not only make strong arguments but also to analytically prove why those arguments matter most in the context of the entire debate, for more clarity and strategies you can explore our Lincoln Douglas, Policy and Public Forum Debates blogs:

Success is based on a great case building. The teams ought to strive towards being clear, extensive, and profound in their presentation.

Not only by arguing parts in a debate is it won, but also by showing why your arguments are significant as compared to those of your opponent.

Teamwork makes the team play a cohesive and strong presentation throughout the debate.

The method of conveyance and the manner are sometimes more important than the merits of the arguments themselves.

The aspect of competitive debate that depends on the impromptu nature of argument-based and does not allow any outside evidence to be shown during the limited period of preparation, therefore, means that good preparation should precede.

There is no doubt that avoiding these traps can significantly enhance one's efficiency and save unnecessary rounds of parliamentary discussions.

Specialize in the national debating organizations that hold tournaments such as WUDC, APDA, and NPDA; they can give you rulebooks and guides for training in deepening your debate skills. Look into the various university programs that offer summer camps and workshops for debate at the collegiate level. Dive into established textbooks in rhetoric, logic, and critical thinking. Practice through constructed drills and mock rounds with peers to apply practical experience.

Parliamentary debate is that form of debating which actually should be very spontaneous, dynamic, and more focused on logical arguments, structure, and eloquent persuasive oratory than on any pre-written evidence. Winning depends on perfect management of the short prep-time, keeping up with a clear three-point structure, and bringing in points with rebuttals and Points of Information. Common mistakes in parliamentary debate, such as time mismanagement or the introduction of new arguments in rebuttal speeches, can be quite significant as far as the judge's final decision is concerned.

The three Ms are the essential segments to judge the performance of a speaker. They are Matter, which is the content, arguments, and evidence; the second is the Manner, which is who, how, style, and eye contact, voice; and the third is Method, which is who, how, structure, and roles of speakers and team.

Core elements are combined in the vital formula of debate. It begins with the Resolution, the subject, two opposing Teams, one Affirmative and one Negative, a definite Structure, speeches and rebuttals, and a Judge who determines which side was more convincing due to logic, evidence, and presentation.

A full and systematic argument generally has four components. The first, Claim, which is your primary assertion or point, followed by Warrant, the logical reason that the claim is valid, followed by Data, evidence, facts, or examples, and Impact, the importance, or (so what) why the argument is important to the resolution.

The first statement helps you give a brief roadmap of your case. It has an interesting hook to draw in, gets straight to the point with what the resolution is and what your team will be arguing, and does a quick summary of the two or three main debate arguments you will be demonstrating during the round.

Subscribe now!

To our newsletter for latest and best offers